In this final part of Financial Choices we will cover managing debt. Debt is a huge part of the finanical world and it isn’t all bad, but it is essential you understand what debt could mean for you and your future.

So, let’s get into it.

Managing debt

Debt isn’t always a bad thing, in that some can help you build your credit history (For instance, having a credit card which you utilise a little each month, but pay off in full on time) and it’s often necessary (eg/ to buy a house or pay for university). We can distinguish between good debt and bad debt.

task

List all the possible ways in which you could borrow. See if you can think of at least 3 different options.

Task One – Options for borrowing money?

List all the possible ways in which you could borrow. See if you can think of at least 3 different options.

Reveal answer

Hopefully you came up with some of the following:

- Family and friends

- Secured loan

- Overdraft

- Personal loan

- Credit card

- Payday loans

The cost of borrowing is determined by the interest rate charged, and the length of time you borrow for. All forms of borrowing are required to display the APR – Annual Percentage Rate. This should allow all forms of borrowing to be easily compared, but in reality it can be complex.

Looking at some specific type of borrowings, pay day loans can charge over 4,000% APR (!), compared to an approximate average of ~20% APR for an overdraft, the next highest form of borrowing. Whereas a loan, depending on the current economic climate, could be anywhere from 4% -> 15%. Payday loans are a form of borrowing which many young people have exposure too without full understanding – being able to understand how quickly the interest can build up illustrates how careful young people (or all people!) need to be with this form of borrowing.

Hopefully this makes it apparent that some debt can be ‘good’ and ‘bad’, both in terms of the cost, but also the use of the money, which we’ll look at next.

Jenny wants to go on holiday with her friends in the summer, but the destination they have agreed on is expensive and unaffordable for her. She doesn’t want to be left out, but would need to borrow the money.

Great work! This scenario could be considered ‘bad debt’. It is raised on a one off basis, with no accompanying ‘asset’, ie/ it is consumed with the holiday, and there is no plan as to how it’ll be repaid.

Ah, better luck next time! This scenario could be considered ‘bad debt’. It is raised on a one off basis, with no accompanying ‘asset’, ie/ it is consumed with the holiday, and there is no plan as to how it’ll be repaid.

Lewis has been getting the bus to work every day for several months, but has figured out that a car would be a cheaper options over the longer term. He cannot afford a car outright so would have to borrow to purchase one.

Great work! This scenario could be considered ‘good debt’, as it mains economic sense over the longer term.

Ah, better luck next time! This scenario could be considered ‘good debt’, as it mains economic sense over the longer term.

Your friend is short of case and cannot borrow anything due to a bad credit score. You don’t have any money to give them but consider borrowing money yourself to lend them to help out.

Great work! This scenario could be considered ‘bad debt’. Whilst the intentions might be good, overstretching yourself to support another is a risky scenario with borrowed money, with no guarantee that it’ll be paid back. When we are in a position to be generous we should be – but this is rarely wise with borrowed money.

Ah, better luck next time! This scenario could be considered ‘bad debt’. Whilst the intentions might be good, overstretching yourself to support another is a risky scenario with borrowed money, with no guarantee that it’ll be paid back. When we are in a position to be generous we should be – but this is rarely wise with borrowed money.

Sarah has been living in rented accommodation for the past 3 years. She has saved up a deposit to buy a house, but will need to borrow a substantial sum for a mortgage in order to buy a suitable property. After performing a detailed budget including one-off expenses and a contingency fund, she works out repayments over the mortgage term are affordable.

Great work! This scenario could be considered ‘good debt’, as it is a well thought through plan that has been budgeted for, and is for the purchase of an ‘asset’, ie/ the property.

Ah, better luck next time! This scenario could be considered ‘good debt’, as it is a well thought through plan that has been budgeted for, and is for the purchase of an ‘asset’, ie/ the property.

How did you find that exercise? Whilst there could be some subjectivity, generally speaking;

- Scenario 1 could be considered ‘bad debt’. It is raised on a one off basis, with no accompanying ‘asset’, ie/ it is consumed with the holiday, and there is no plan as to how it’ll be repaid.

- Scenario 2 could be considered ‘good debt’, as it mains economic sense over the longer term.

- Scenario 3 could be considered ‘bad debt’. Whilst the intentions might be good, overstretching yourself to support another is a risky scenario with borrowed money, with no guarantee that it’ll be paid back. When we are in a position to be generous we should be – but this is rarely wise with borrowed money.

- Scenario 4 could be considered ‘good debt’, as it is a well thought through plan that has been budgeted for, and is for the purchase of an ‘asset’, ie/ the property.

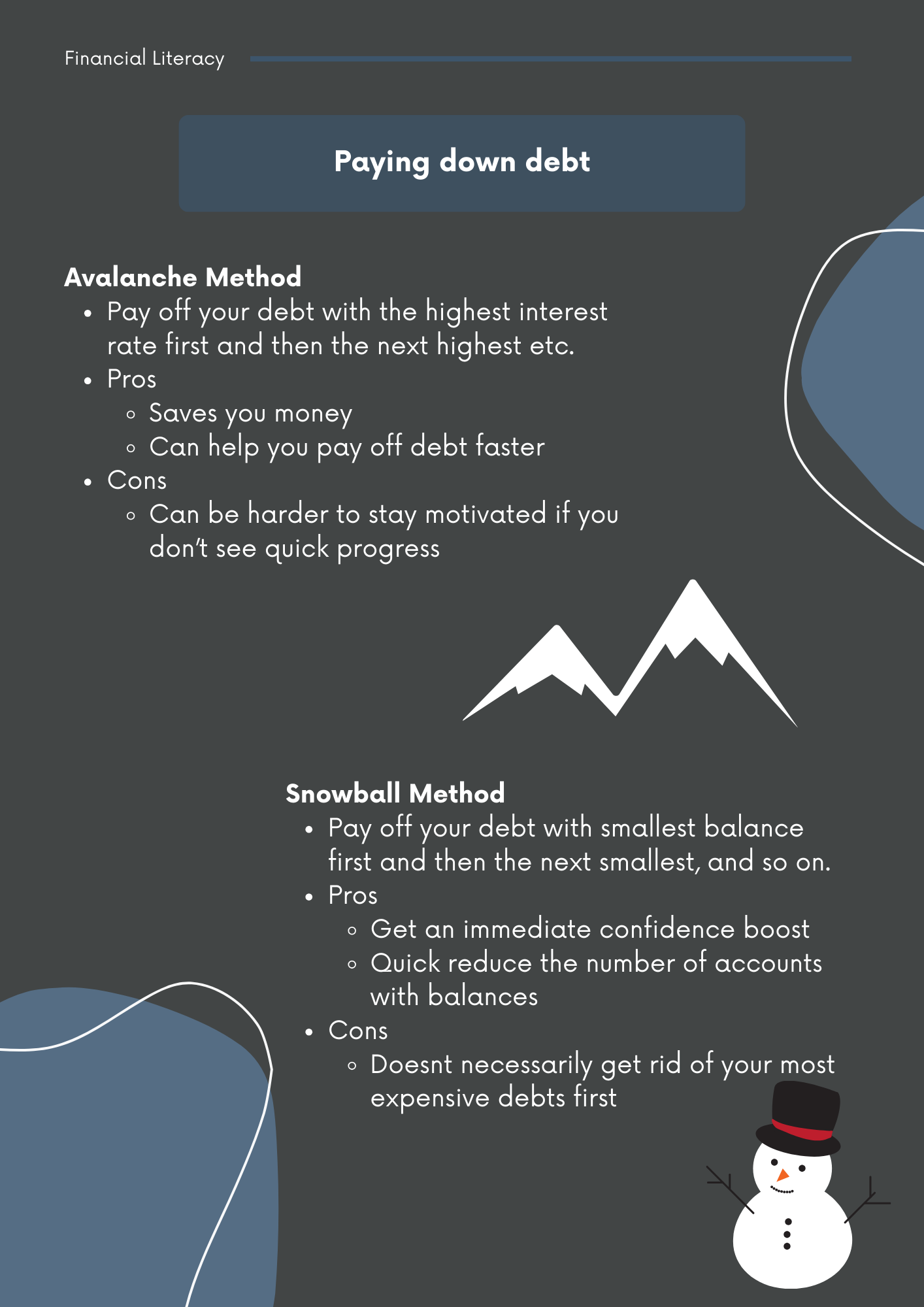

Going back to what we learned about budgeting, once you have an emergency fund established, and are on track with your saving goals, before you begin to invest it’s sensible to consider paying off any debts. Debt can become out of control – like if you’re paying more in interest on something than it cost in the first place, as per the debt spiral illustrated in the budget cheat sheet.

Paying down debt will add financial security and provide flexibility when deciding what to do with your money afterward. But if you have a large debt balance, it can be hard to feel like you’re making a real dent in the amount owed.

Whilst there is no way to make your debts shrink overnight, there are strategies that can help ensure you’re making consistent progress.

Reducing your debt load can help you to;

- Improve financial flexibility

- Reduce stress

- Increase your credit score

- Give you extra money for discretionary spend, saving or investing.

The interest rate you pay on the vast majority of short-term debt is likely to be many times higher than the rate of return on any investment you make. You should prioritise paying off things like credit card debt and payday loans before making any investments. There are largely two approaches to paying down debt;

If you do have any debt or continue to have debt, make sure you don’t miss making any payments ahead of their due date – any penalty fees/charges and the interest you incur will more than offset any gains you’d make on an investment. Missing a payment will also damage your credit score, making it harder and more expensive to get credit if you ever need it in future.

Note that if you are in significant debt and there is no clear route out, there are many specialists to talk to for free, the most prominent of which would be Citizens Advice. If your debt is unmanageable or is affecting your mental health, do not hesitate to get assistance

Financial ethics

Splitting bills

When living with others, knowing how to split rent and utility bills fairly seems like a no-brainer…until you try and do it. While lost friendships could undoubtedly be a shame, other significant consequences can come about if you’re not candid about cash with fellow housemates. Whoever’s named on the bill is liable for the entire sum should the account fall into arrears. There are several ways to split bills, including straight down the middle, based upon income, based upon rooms or usage – overall it doesn’t really matter. What’s important is agreeing the approach up front – talk it through before moving in. Making sure that everyone is explicitly aware of what they’re expected to pay, when it’ll be due, and who they’ll need to pay it to now will save any headaches later on.

Should the worst happen and one of your housemates gets behind on the bills, or flat out refuses to pay, things can get a little tricky. Unfortunately, the legal aspect of such situations isn’t straightforward either. Refer to ‘Problems in Shared Accommodation from the Citizens Advice Bureau’, for further information here.

Money Mule

Money laundering is the process by which the proceeds of crime, such as illegally obtained funds and property, are moved by criminals to make them appear legitimate. These proceeds can come from crimes such as modern slavery (including human trafficking), drug trafficking and fraud.

Money muling is when an individual, commonly referred to as a ‘money mule’, moves the proceeds of crime on behalf of criminals, sometimes in exchange for payment or other benefit. They help hide the origin of illicit funds in various ways, including moving them through their own bank account (or multiple accounts), buying and selling cryptocurrencies, or withdrawing cash and handing it over.

Money muling is a type of money laundering, which is a criminal offence. There are longterm legal and financial consequences for those knowingly and willingly involved. These include, but are not limited to:

• Up to 14 years in prison.

• Being flagged as involved in illegal activity on a banking-sector wide database. This can lead to:

- The closure of bank accounts.

- Existing loans or credit facilities being made payable immediately.

- Difficulty opening new accounts and applying for credit (including mobile phone contracts, student loans, and mortgages).

- Issues trying to get jobs in the future.

- Dismissal from higher education and professional bodies.

Some people may unknowingly become involved in this type of money laundering. For example, criminals might manipulate them into moving money through their account as part of a romance scam or use stolen documents to fraudulently open accounts in their name. Circumstances such as these are taken into account by law enforcement and banks.

The Home Office has published guidance on money laundering-linked financial exploitation and how to react when you suspect someone may be a victim; click here for details.

Age of getting a job

You can work and earn money from the age of 13, but there are strict rules around how young people aged under 16 can work.

Between the ages of 13-16, its not allowed for work to be during school hours. Work can be maximum two hours on a school day or a Sunday. Total for the week must be no more than 12 hours during term time.

During school holidays, work can be a maximum of 25 hours a week for ages 13-14, and 35 hours for ages 15-16. However, you can’t work more than eight hours a day during holidays or Saturdays.

Between the ages of 16-18, work cannot be for longer than eight hours in a 24-hour period, or for more than 40 hours a week. You are entitled to a 30-minute break when you work for more than four and a half hours.”

Being an ethical consumer

Companies spend billions on advertising, marketing and teaching their staff to sell – while consumers get no buyers’ training. This imbalance could be devastating to the wellbeing of millions of people; and we see scams, mis-selling, poor decisions and over-indebtedness in abundance.

Many companies have very questionable practices even in todays day in age, whether than be exploitative labour, environmental impact or dubious tax practices. Ethical consumerism is all about choosing goods that are ethically sourced, ethically made and ethically distributed. When enough consumers shop in an ethically conscious way, it can cause companies to take notice and address their supply chain practices. When we don’t have a lot of disposable income, which often is the case when we are young, it can be hard to consider these matters, and cost is often the primary determinant of where and what we shop. It is important to be aware of these issues regardless – even in the scenario that we cant do a great deal now, at some stage we will have more choice and flexibility, at which point we can closer align our spending habits to our moral values.

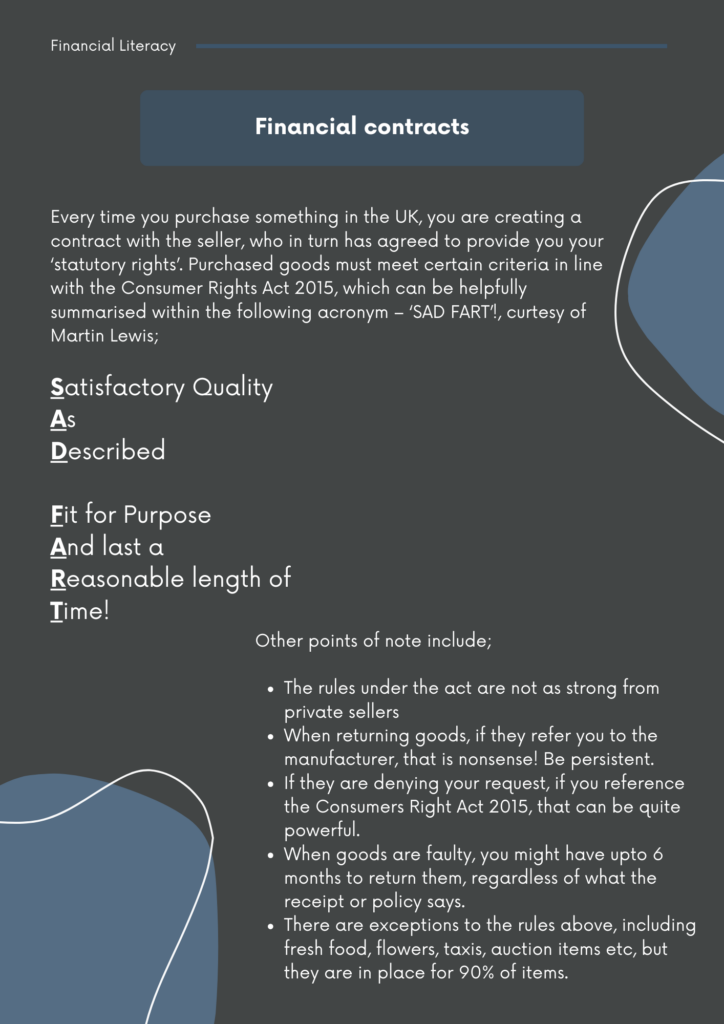

Snapshot of consumer rights and financial contracts

Gambling

Gambling is all around young people today – from advertising during sports events, and the behaviour and habits of reality TV stars, through to the betting shops on our high-streets.

And it is a popular pursuit amongst Britons, with at least two thirds of the population spending money on a gambling activity in the last year. While for many people gambling is a pleasurable activity done in moderation, for a minority it can lead to substantial problems – financially, psychologically, and socially.

Evidence also shows that many school students are involved in some form of gambling-related activity – such as playing cards for money and betting with friends – long before they are legally old enough to place bets online or at the local bookies, or enter a casino.

The vast majority of gambling has a minimum age of 18 for all players in the UK. There are some small exceptions for low stake activities such as fruit machines, coin pushers / penny falls or crane grabs.

All gambling is very high risk – the chances of losing money are far greater than winning it. This is how organisations in the gambling industry make their money – ‘the house always wins’. The most common form of gambling in the UK is the National Lottery, with 30% of people over 18 taking part. This is despite the chance of winning the jackpot being around 1 in 45 million!”Losing money through gambling may impact on your ability to pay your bills or keep to contracts that you have agreed to. The potential losses from taking a financial risk can cause stress, which can have a serious effect on your health

GIST – good ideas for starting things…

- Download our free ‘Budgeting cheat sheet’ and work through it to reflect on your current financial situation.

- Follow our money saving hacks to the right to make the money you have go further.

Want to learn more?

- Access this Budget Planner spreadsheet from the money saving expert

- Learn about your responsibilities when renting from the money saving expert too

- UCAS share some helpful information about bursaries and scholarships related to further education

- Understand more about problems that can arise in shared accommodation